Except article from College of Agriculture and Life Sciences, The University of Arizona

When most U.S. citizens think about water shortages ├óÔé¼ÔÇØ if they think about them at all ├óÔé¼ÔÇØ they think about a local problem, possibly in their town or city, maybe their state or region. We don’t usually regard such problems as particularly worrisome, sharing confidence that the situation will be readily handled by investment in infrastructure, conservation, or other management strategies. Whatever water feuds arise, e.g., between Arizona and California, we expect to be resolved through negotiations or in the courtroom.

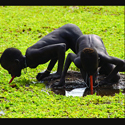

But shift from a local to a global water perspective, and the terms dramatically change. The World Bank reports that 80 countries now have water shortages that threaten health and economies while 40 percent of the world ├óÔé¼ÔÇØ more than 2 billion people ├óÔé¼ÔÇØ have no access to clean water or sanitation. In this context, we cannot expect water conflicts to always be amenably resolved.

Consider: More than a dozen nations receive most of their water from rivers that cross borders of neighboring countries viewed as hostile. These include Botswana, Bulgaria, Cambodia, the Congo, Gambia, the Sudan, and Syria, all of whom receive 75 percent or more of their fresh water from the river flow of often hostile upstream neighbors.

In the Middle East, a region marked by hostility between nations, obtaining adequate water supplies is a high political priority. For example, water has been a contentious issue in recent negotiations between Israel and Syria. In recent years, Iraq, Syria and Turkey have exchanged verbal threats over their use of shared rivers. (It should come as no surprise to learn that the words “river” and “rival” share the same Latin root; a rival is “someone who shares the same stream.”)

More frequently water is being likened to another resource that quickened global tensions when its supplies were threatened. A story in The Financial Times of London began: “Water, like energy in the late 1970s, will probably become the most critical natural resource issue facing most parts of the world by the start of the next century.” This analogy is also reflected in the oft-repeated observation that water will likely replace oil as a future cause of war between nations.

Global water problems are attracting increasing attention, not just at the international level, but also within the United States, in its popular press, in natural resource journals and as the subject of books. Former Sen. Paul Simon from Illinois recently authored Tapped Out: The Coming World Crisis in Water and What We Can Do About it. A book for the general, non-specialized audience, Simon’s publication sounds an alarm about the approaching crisis. “Within a few years, a water crisis of catastrophic proportions will explode upon us ├óÔé¼ÔÇØ unless aroused citizens … demand of their leadership actions reflecting vision, understanding and courage.”

A prime cause of the global water concern is the ever-increasing world population. As populations grow, industrial, agricultural and individual water demands escalate. According to the World Bank, world-wide demand for water is doubling every 21 years, more in some regions. Water supply cannot remotely keep pace with demand, as populations soar and cities explode.

Population growth alone does not account for increased water demand. Since 1900, there has been a six-fold increase in water use for only a two-fold increase in population size. This reflects greater water usage associated with rising standards of living (e.g., diets containing less grain and more meat). It also reflects potentially unsustainable levels of irrigated agriculture. (See sidebar.) World population has recently reached six billion and United Nation’s projections indicate nine billion by 2050. What water supplies will be available for this expanding population?

Meanwhile many countries suffer accelerating desertification. Water quality is deteriorating in many areas of the developing world as population increases and salinity caused by industrial farming and over-extraction rises. About 95 percent of the world’s cities still dump raw sewage into their waters.

Climate change represents a wild card in this developing scenario. If, in fact, climate change is occurring ├óÔé¼ÔÇØ and most experts now concur that it is ├óÔé¼ÔÇØ what effect will it have on water resources? Some experts claim climate change has the potential to worsen an already gloomy situation. With higher temperatures and more rapid melting of winter snowpacks, less water supplies will be available to farms and cities during summer months when demand is high..

A technological solution that some believe would provide ample supplies of additional water resources is desalination. Some researchers fault the United States for not providing more support for desalination research. Once the world leader in such research, this country has abdicated its role, to Saudi Arabia, Israel and Japan. There are approximately 11,000 desalination plants in 120 nations in the world, 60 percent of them in the Middle East.

Others argue that a market approach to water management would help resolve the situation by putting matters on a businesslike footing. They say such an approach would help mitigate the political and security tensions that exacerbate international affairs. For example, the Harvard Middle East Water Project wants to assign a value to water, rather than treat rivers and streams as some kind of free natural commodity, like air.

Other strategies to confront the growing global water problem include slowing population growth, reducing pollution, better management of present supply and demand and, of course, not to be overlooked, water conservation. As Sandra Postel writes in her book, Last Oasis, “Doing more with less is the first and easiest step along the path toward water security.”

Ultimately, however, an awareness of the global water crisis should serve to put our own water concerns in perspective. Whether our current activity is evaluating Arizona’s Ground Water Management Act or, at a more personal level, deciding whether to plant water-conserving vegetation, the wiser choice would likely be made, if guided by an awareness that water is a very scarce and valuable natural resource.